When we think about what shaped our life trajectory, we often focus on the way our parents raised us. But what about our siblings? What role do they play in who we become?

My guest today makes the case that siblings may be just as influential as parents in impacting how we turn out.

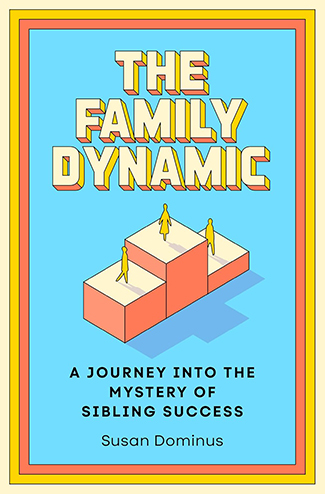

Her name is Susan Dominus, and she’s a journalist and the author of The Family Dynamic: A Journey into the Mystery of Sibling Success. Susan and I start our conversation by unpacking the broader question of what drives human development more — nature or nurture. We then dig into how siblings shape us, from the impact of birth order to how rivalry can raise our ambitions and alter our life paths. Along the way, we also explore the influence parents do have on their kids — and why it may not be as strong as we often think.

Connect With Susan Dominus

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Transcript

Brett McKay:

Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. When we think about what shaped our life trajectory, we often focus on the way our parents raised us. Well, what about our siblings? What role do they play in who we become? My guest today makes the case that siblings may be just as influential as parents in impacting how we turn out. Her name is Susan Dominus and she’s a journalist and the author of the Family Dynamic: A Journey into the Mystery of Sibling Success. Susan and I start our conversation by unpacking the broader question of what drives human development, more nature or nurture. We then dig into how siblings shape us from the impact of birth order to how rivalry can raise our ambitions and alter our life paths. Along the way, we also explore the influence parents do have on their kids and why it may not be as strong as we often think. After the show’s over, check out our show notes at aom.is/familydynamic. All right, Susan Dominus, welcome to the show.

Susan Dominus:

Thank you so much for having me. I’m very happy to be here. So

Brett McKay:

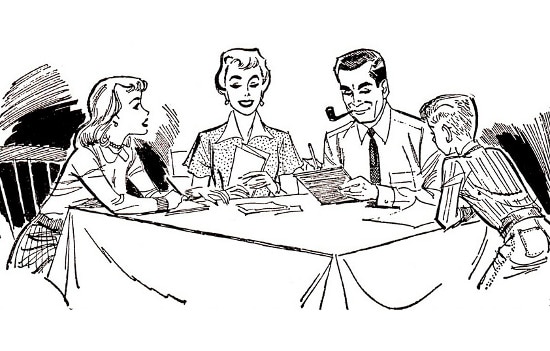

You wrote a book called The Family Dynamic where you explore how family culture and how siblings affect us even into adulthood. And you start off the book talking about a childhood memory of having dinner with a friend’s family, and you felt incredibly out of place when the father of your friend turned to you and asked you to solve this math problem. How did that moment lead to you researching and writing a book about family culture and the role siblings play in raising each other?

Susan Dominus:

Well, I guess I should first say the book is called The Family Dynamic, and it’s about the way that siblings affect each other and their paths to success. It is also about the way that parents affect kids. And that moment was really powerful for me because I just really had a sense of how different family cultures could be and the family culture in that family was very clearly around skill learning and achievement and mental acuity and just a kind of constant teaching environment. And although I grew up in a very warm and supportive household, that wasn’t really the energy in the household. I don’t think my parents saw themselves as educators of us. And so on the one hand, I was really relieved to go back home where my parents really just had expected us at least at meals to chew with our mouths closed.

But at the same time, I did think, well, the Goldie boys are better at math than I am. Is that because they’re just better at math or is that because they’ve grown up doing these math problems and who could I have been if I had been growing up in a household where we were doing math in our heads for fun after dessert and talking about current events at the table and just having a slightly more kind of elevated learning environment? It’s not for everyone and not every kid would want that, but I was like an eager beaver little overachiever, and part of me thought maybe I was missing out.

Brett McKay:

And you highlight other famous families that had a family culture around the dinner table that might seem like overkill for a lot of families. Like the Kennedys. Joe Kennedy would famously tell his kids like, you got to prepare some presentation about this foreign policy thing that’s debating in Congress and present it to the family at dinner.

Susan Dominus:

And it wasn’t just that he had them present to the group. He had all the other siblings prepare too, so that they could grill the sibling who was in the hot seat that day or that dinner. So that’s how you see. I think the way that it’s hard to separate out sibling dynamics from parent child dynamics. The parent was setting this tone for performance and achievement, but there was also clearly a competition among the siblings that he thought could be used to harness high performance in his kids.

Brett McKay:

He wanted one of his kids to be president.

Susan Dominus:

He definitely thought that one of his kids would be president. He definitely thought his firstborn would be president, who sadly and tragically died young serving in the military. But it was always a goal. It was always something spoken about. So that also gets at the way that expectations can really play a role in what happens in families.

Brett McKay:

So you’re a mother of twins, correct?

Susan Dominus:

I am, yes.

Brett McKay:

So how did that parental experience drive your investigation into sibling dynamics?

Susan Dominus:

I think that parents of twins, specifically fraternal twins are experts in realizing personally how much of their children’s upbringing is affected by nature and how much of it is really nurture. Because when you have fraternal twins and you are reading them the same stories every single night and you are having the same dinner table conversations and you’re sending them to the same preschools and you’re feeding them the same broccoli, and one of them turns out to be a tremendous athlete and tennis player. This is theoretical. Neither of my kids plays that much tennis and the other one of them is obsessed with art. You could say that there is some differentiation going on there, but probably those parents also saw those signs when the kids were really, really little that as soon as they could talk, one of them was interested in pictures and wanted to play with paints all the time, and the other one couldn’t stay away from tennis balls. I mean, in my kids, I think I saw the seeds of who they were so early. So it’s a very humbling experience as a parent, you realize you can’t take credit for the stuff that you’re proud of because maybe the other one doesn’t have that quality. But you also can’t blame yourself that much for the things that go wrong because you see that so much of who kids are is what they’re bringing from the moment they’re born.

Brett McKay:

Yeah, I’ve noticed that with my own kids have a son and a daughter, and they’ve had the exact same, I mean, we’re going to talk about this. It’s probably not the exact same family experience. There’s differences whenever you had a second sibling. And our lives have changed as we’ve gotten older as a family, but we’re doing the exact same thing. We’re teaching the exact same things. We have the same rules, but completely different personalities, and there’s nothing we can really do about that.

Susan Dominus:

Of course, that’s really magnified in friends. You are raising them in real time at the same time too. It’s not like, oh, I was a different person. I was two years older when I had learned some things along the way. It’s all happening right in front of you. I do think it’s possible that there are magnifying effects. I think sometimes parents, and there’s some research to support this that they decide one kid is the academic kid and then they shower that kid with encouragement in academic pursuits, less so the other child, and then you have a kind of cascading effect or an amplifying effect, I guess you could say.

Brett McKay:

So in this book, The Family Dynamic, you highlight several different families that have managed to produce several highly successful and ambitious adults. You decide to focus on high performer adults and the dynamic they had as kids.

Susan Dominus:

The funny thing is I would say that I’m as interested in generic achievement as any other parent in my demographic. I think I’m a little more interested than other people maybe in what makes people defy the odds, what makes people have big, bold thoughts, what makes people feel that they uniquely can bring something to the table that no one else has brought? What makes people feel like they can change the world, have the confidence to feel that way, and then have the skills to go ahead and execute it. So it wasn’t a book just about generic achievement, it was really a book about how do you get your kids to dream really big, whatever their talents are, how do you foster that sense of confidence and possibility? I think that’s something that I really craved to be honest as a kid myself, my parents, my mom in particular grew up very, very poor and was a very cautious person and very much a worrier. And just as in some households I thought like, gee, what would it have been like to grow up in a household where we did math around the table? I think I often thought, what would it be like to grow up in one of those families where there’s a sense of irreverence, a sense that just because other people have tried and failed doesn’t mean that you won’t succeed. I’m very interested in that energy.

Brett McKay:

So besides these living families that you highlight and look at in your book, you also use the Bronte sisters as your go-to family to figure out what makes people or siblings who all have these big ambitions, what makes them tick. For those who aren’t familiar with the Brontes, who were they?

Susan Dominus:

So there were actually many Bronte siblings. Several of them died young, but the most famous Brontes were Charlotte and Emily Bronte. Charlotte Bronte wrote Jane Eyre, which is one of the greatest novels of the 19th century, and her sister, Emily Bronte wrote Wuthering Heights. Another great, Anne Bronte, wrote a couple of exquisite novels as well that were also really original. I mean, that’s what these three novels all had in common is, or these three novelists I should say. Each of them wrote unique, beautiful works of literature, and each of these books were completely different from each other. They were unique even within the family. Wuthering Heights is this great kind of torrid, romantic, almost supernatural tale, really very gothic. And Jane Eyre has a tremendous amount of realism, but is told from the point of view of this very modest and humble and not particularly beautiful governance, which was a perspective that had never really been represented in novel form in just that way. So the sisters totally influenced each other. They also had a brother who had a huge influence on them, and they’re probably some of the most famous siblings in history.

Brett McKay:

And you talk about how the sisters encourage each other. I forgot which one it was, but there was one sister who found the other sister’s writing, and she told her, Hey, this is really good. And at first the sister was kind of mad like, Hey, what are you doing? Rummaging through my stuff like that, typical sibling spat. But the other sisters had been writing too, and they decided that maybe they could get something published if they worked together.

Susan Dominus:

That’s exactly what happened. Charlotte Bronte, I think was sort of at her wit’s end. She was a bust as a governess. They had all thought that their brother was going to be the one who made it big. And by then he was a total burnout addict, unfortunately. And I think Charlotte was trying to figure out what they were going to do. They’d all been avid writers for fun from their very earliest years. And the way the story goes, I mean, who knows if it’s true, but she wrote about it in the forward to one of her books. She stumbled on her sister’s poetry. This is Emily Bronte’s Poetry, thought it was tremendous and realized that if the three sisters combined their poetry, they could get a book out and maybe make a little money. And the book didn’t. I think it sold literally two copies, but it was well reviewed and I think it gave them the confidence to think they could really keep going. But I always say that from the very beginning, their artistic careers were literally bound up with each other. They were all bound up in the same book. And without the three of them probably it wouldn’t have happened for any one of them

Brett McKay:

Because they’re also battling. There are women in the 19th century, and there’s the expectation like, well, you don’t write, your goal is to become a mother, a wife, and their father. It seems like their father kind of inculcated be ambitious, but for women, your ambition is to be an awesome wife and mother.

Susan Dominus:

I think that’s exactly right. On the one hand, he encouraged them to read widely, much more widely than most men encouraged young women to read at the time. And he himself loved to write, even though he wasn’t terribly good at it. He had other skills, but he definitely, from what we can tell from correspondence, he seemed to encourage them really to focus on the practical and was afraid of his daughters getting entirely lost in a dream world, both of fiction and a dream world of unrealistic ambitions for themselves.

Brett McKay:

So the sisters had to, they were relying on each other to be each other’s boosters for this.

Susan Dominus:

No one else was encouraging those young women to be writers particularly. No.

Brett McKay:

Yeah. So you talk about the Brontes as a way of showing how both someone’s siblings and parents can shape their life trajectory. And we’re going to talk about both of those influences today. But let’s first take a step back and look at the central question of your book, which is, how much influence does a child’s environment or upbringing really have on how they turn out anyway? I mean, that’s the question. It’s the old nature versus nurture debate. After pouring over the research and talking to experts, what conclusion did you reach on that question?

Susan Dominus:

The easiest way to put it is that 50% of the difference among individuals can be explained by nurture, and 50% of that difference can be explained by nature. What people get wrong is that they think that nurture is basically parenting. So they overemphasize the role of parenting and put it right up there with nature, meaning how you were born and what you came into the world with. But nurture is not just parenting. Nurture is everything in your environment. It’s your siblings, it’s the town you live in. It’s where your bedroom is located in the house, and whether it got a lot of sun or not, it’s who your next door neighbor is. It’s what nature documentary you watched when you were seven years old that lit you on fire. There’s so much in your environment that shapes who you are, and so much of that is random. And in a way, the most important thing a parent does is determine whether or not their child’s going to go to college. Because at least in the past, that has been one of the single biggest drivers of how people fare in life in terms of economics. And economics is highly tied to longevity, education, highly tied to marriage stability, all these things. So outside of education though, parenting is just one of a bazillion things that happened to us over the course of our lives that are part of nurture.

Brett McKay:

And something that researchers have done to try to figure out nature versus nurture is do these twin studies. And so what these twin studies do, they’ll find twins who were separated at birth for some reason and got moved to different locations completely and said, okay, how did their lives turn out? How similar and how different are these people who they’re genetically the same, but they grew up in different environments? What do we learn from those studies?

Susan Dominus:

There’s a lot of critique of that research because a lot of it’s anecdotal and it’s really hard to, as you can imagine, the case study, it’s not nothing, but it’s not vast. So they study twins who are raised apart, but they also can learn a little bit about nature and nurture by comparing how similar identical twins are to each other. And then looking at fraternal twins and seeing how much like each other they are as well. But going back to the twins who were separated at birth, they do often find that those twins eventually end up in pretty similar places, income wise, education wise, marital status wise, regardless of how they were raised. So there’s some research that finds that, let’s say you were adopted into a family in which the parents stayed married, but your own parents whom you never even knew divorced, that child is probably going to have a divorce rate that’s more like the genetic parent than the one who raised them.

Brett McKay:

Interesting. And you talked about this one interesting study. It’s not probably very applicable to humans, but it’s with mice, laboratory mice where the scientists will basically create a ton of mice that are genetically the same, but then they’ll look at how do these mice, these genetically same mice end up? You put them in different environments, they can end up pretty different because the way they interact with the environment changes the kind of mouse they become.

Susan Dominus:

I love that you brought up that study. It was really a study that was intended to look at neuroplasticity in mice, but what it found ultimately was just what you said. They took these clones, these mice are clones, they are each other, and they put them into this kind of fun house environment at birth, essentially. And just by happenstance, some mice were near a fun toy and some weren’t and made a move towards one randomly and another one didn’t. And those minor differences really, really seemed to set them on different paths over time. And there’s just this endless iteration, we’re all new inventions of ourselves that come of the combination of what we came to be put on this earth with and how that interacts with the 10,000 things that happen to us over the course of a day. So we’re like almost a whole new creature every day, and that we’re being shaped by our environment, which is interacting with what we brought to the table in the first place.

Brett McKay:

So if you’re an identical twin, you might have different friends than your identical twin sibling, and that’s going to affect the kind of person you’re going to have. Maybe different interests maybe have different goals or ambitions in life than your other sibling.

Susan Dominus:

That’s exactly right. I mean, there is more similarity among identical twins for things like personality traits, but it’s not perfect. It’s not a perfect concordance. It’s not a hundred percent. So that’s how we know that the environment is really, really powerful.

Brett McKay:

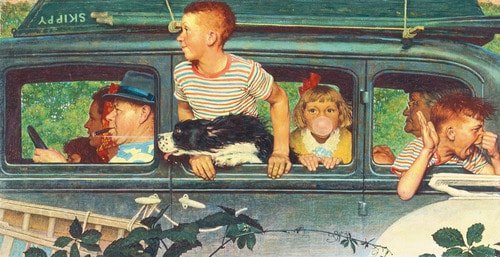

Let’s talk about how siblings can affect how you turn out. And I think there’s this popular idea that people like to talk about around the kitchen table or when they’re with friends, and that’s birth order or sibling order. Does birth order have an effect on personalities and outcomes? Cause I mean, I think typically there’s this stereotype of like, well, older siblings are going to be more successful. They’re ambitious, they’re kind of seen as the leader. The younger kid is seen as less motivated, more the fun lover. What does your research tell us about how birth order affects how children turn out?

Susan Dominus:

There’s two really prominent findings that seem almost contradictory, but I’ll lay them out for you. One of the things that research finds so consistently is that the oldest child in the family tends to have the highest IQ, tends to have the most cognitive firepower that shows up over and over again. And people think the reason for that is that they are the only ones in their family, the only child in their family who had the benefit of their parents’ exclusive attention when they were young. And it’s one of the best arguments we have for the power of enrichment, right? It’s a great argument for the power of environment. And in fact, there’s also something about a sibling effect in there. We know that oldest children who have younger siblings do better cognitively than only children. So there’s something about the fact that they are interacting with younger siblings that is thought to consolidate their knowledge or enhance their abilities.

Somehow the mechanisms are not well understood, but there’s something about being the oldest sibling that gives you a cognitive edge relative to younger siblings and even relative to only children. That said, there isn’t a ton of research that finds that oldest siblings have different personalities from younger siblings that you can reliably predict that the oldest sibling is going to be, let’s say, the most conscientious. A lot of the research on sibling order that was done would ask kids in a family who’s the most conscientious in your family, let’s say, where they would ask them to rate their siblings conscientiousness scores. If you are 25 and your oldest sibling is 32, yeah, they look like the most conscientious one in the family. They are more mature. The oldest child, as one of the people I interviewed said, will always be the oldest child, which is to say the most responsible because they’re older, but they’re not necessarily particularly conscientious relative to other people their age. So a lot of the research was conducted in ways that were imperfect, and the best conducted studies on sibling order finds that there are not a lot of personality differences that correlate with birth order. I know it’s a shock, but it’s true.

And you sort of know it because you may have even had this experience where somebody will say to you, well, I am the middle child, so I’m the peacemaker, and you kind of nod your hip and you’re like, yeah, yeah. But then you meet somebody else who’s a middle child and they say, yeah, I was a middle child. I was always forgotten. So I’ve always been kind of a pain in the neck. And they think that their birth order explains everything, but it’s like astrology. You can tell yourself any story you want as a result of your birth order, but birth order, let’s say, as we’ve already discussed, your environment is multifactorial. So the idea that your birth order alone would place such an outsized role in your personality, it doesn’t really make sense.

Brett McKay:

Okay, so birth order may not have as large of effect as we often think, but it can affect the IQ of the firstborn. And as you mentioned, that’s because parents typically invest more time and energy in their first kid because they’ve got more time and bandwidth to pay attention to them because they’re the only kid. But as you add a second, third, fourth kid, the parent’s attention gets split between the kids. But what’s interesting is that there’s research that suggests that heavy investment in the older child can actually trickle down and benefit the younger children.

Susan Dominus:

Well, that’s the idea is that the way the economists look at that is they say, oh, it’s a rational choice to invest more in the oldest child because we know there are trickle down effects when the oldest siblings do well, that tends to elevate the performances of the younger siblings. So if you can maximize performance of the oldest sibling, you’ve already done your work, right? That’s going to affect the younger kids even if you don’t do anything else. So it’s a funny economic analysis. I don’t think anybody consciously thinks that way, but it does sort of make sense.

Brett McKay:

So in the families you studied, how much influence did older siblings have on younger ones, both positively and negatively?

Susan Dominus:

I think that I saw that happen a lot in the families I wrote about. The Meia family, for example, is this really prominent family of Mexican American jurist and philanthropists, really prominent figures at a national level. And they grew up in a very disadvantaged community in Kansas City, Kansas, or at least their home was very humble. And their oldest sibling went to college, obviously before they did. His name was Alfred, and he was the first in the family to go to college, and he got to Kansas University before any of them did. And they all say that because he was there and had already navigated financial aid and had already made friends and gotten into a prestigious fraternity, it made it so much easier for them when they got there. Now things didn’t work out as well in terms of conventional achievement for Alfred because he was the first one there, and he was kind of an only at the time, and he was the only Mexican American kid in a predominantly white fraternity.

He felt a lot of financial pressure. He felt really alienated. He ended up dropping out of University of Kansas and keeping it a secret from his siblings. And none of them ever spoke about it, but they all credit him with their ability to succeed in that environment because I see it in my own kids. Going to a really big state school can be a very overwhelming experience. You don’t know how to get into the good classes. You don’t know what the good classes are. If there’s somebody who’s there before you paving the way, it is immensely more helpful. So older siblings can really see also talent in their younger siblings that I think parents don’t always recognize just because they’re not in the same environment that kids are immersed in. And also, I think that older siblings can see the future in a way that parents sometimes can’t.

And so they can be really great sources of vision and advice. And also adolescents in particular would much rather get advice from a sibling than a parent. I often quote Lisa Damour, who’s a wonderful psychologist and speaker who says that parenting advice when given to an adolescent, she calls it the kiss of death advice. If you want your kid to do something and they’re 16 years old, the best way to turn them off, the idea is to suggest it. So in my own life, having an older brother was really influential for me because I looked up to him and when he suggested I do something, I took it pretty seriously.

Brett McKay:

So older siblings can pave the way for the younger ones, and they can give each other advice or suggestions that can steer them in certain directions because siblings see each other in a way parents can’t. What role does rivalry and competition play in the effect that the older sibling has on younger siblings?

Susan Dominus:

I think you see it most closely in a family wrote about called the Graffs, the three siblings there are Adam Graff, who’s this tremendous serial healthcare entrepreneur, a younger sister Lauren, who has written many lauded novels and is many times National Book Award finalist, one of the great novelists of our generation. And then their youngest sibling, Sarah True, was an Olympic triathlete and is currently an Iron Man champion. So they’re really an extraordinary family. But I think when they were kids, Lauren and Adam jostled quite a bit in her recollection, of course, because the older brother, he doesn’t remember very much of it at all. But Lauren once told me that a huge part of her motivation came from a kind of fury that burned in her about feeling underestimated by her brother.

Brett McKay:

So yeah, the rivalry can really catapult them to success. It could be a driver, and I think you can see that with the Williams sisters, Venus and Serena.

Susan Dominus:

Well, I think in a way that Williams sisters, what drove them was having somebody as good as them to practice off of all the time. But I’m sure the rivalry was there too, but it was also just kind of proximity to greatness mean. And obviously the Kennedy father thought that in cultivating that rivalry among the siblings, he would push them to greater heights. Somebody said to me at a party recently, oh, now in my daughter’s fight, I don’t feel so bad about it. I think maybe something positive is coming out of it, not a bad spin. I think it’s also just a calculation every parent makes. What’s more important? Is it more important to you that your kids get along or is it more important that they succeed even if you could control how any of those things interact, which is unlikely. It was just an interesting reflection.

Brett McKay:

Another dynamic that sibling rivalry can create besides pushing siblings to achieve more is just pushing sibling to differentiate themselves within the family. One sibling became an entrepreneur, another one became a writer, and then another one became an athlete. And Lauren, the novelist, she said she became a huge reader because her older brother wouldn’t let her talk. But it seems like they were each really trying to carve out a distinct lane for themselves. So siblings could differentiate themselves by leaning into distinct personality traits, different interests sometimes like choosing a different high achieving path like the Groffs did. But I’m curious, did you find any instances where one sibling, maybe not consciously, but they chose a less, we’ll say, less optimal life path in order to differentiate themselves from a high achieving sibling?

Susan Dominus:

I’m sure that that happens. I think that there probably are families in which if the sibling feels that they can’t compete at the level that the other siblings are performing, that they just stop trying. It feels like a familiar dynamic. I can’t say that I came across any families like that over the course of my reporting. I mean, I was looking for families where almost everybody was high achieving, but I do feel like that dynamic seems familiar.

Brett McKay:

Yeah, I think it might happen. I thought it was interesting. You talked about, I think there was one family where a dead sibling affects the living siblings, and the living siblings didn’t even meet or know their dead sibling. Tell us about that. I thought it was interesting.

Susan Dominus:

Yeah, I think there used to be a term, a theoretical psychological term called the replacement child. And there was this idea that when a child dies very, very young, that child becomes he or she of sainted memory. They never had the chance to grow up to be somebody who disappointed their parents or through a tantrum or trashed the family car or dropped out of law school. They die when they’re all adorableness and they are all potential and when they die very young. And so I think being a sibling in a family where a sibling has died and all you’ve ever heard about is how perfect that child was. I heard two things from surviving siblings. One was, we didn’t want to be a burden to our parents. We didn’t want to cause them pain. I think that’s true also sometimes in families where one of the children is severely disabled. So there’s this pressure to not be another source of pain in your parents’ life, but rather source of joy and pride and ease. But I also think that when you sort of deconstruct what they are saying, I think there also is a sense, a keen sense of awareness of how beloved this other child was and a desire to live up to that reputation.

Brett McKay:

I think typically when we think about sibling dynamics, we think of when we were kids, you’re all in the same house under the same rules. You’re experiencing mom and dad at the same time, but eventually you get older and you guys go your separate ways, oftentimes different parts of the country, and we stop thinking about the sibling dynamic. It’s like, oh, I don’t see my sibling all that often except at maybe Christmas or Thanksgiving. How does the sibling dynamic continue even into adulthood while adult siblings are separated from each other?

Susan Dominus:

It’s interesting, I reported this book over so many years that I really had a sense of how sibling dynamics do play out over time. So for example, one of the families I wrote about, there was some distance among the siblings and then the parents got very sick. Often that can be a source of tension among siblings, but then when people start to get older and the parents aren’t there anymore, then you also really look out for each other’s health in a new way, and that can bring you closer to whether you ever intended it or not. And so I think sibling dynamics change over time and in a way that is both predictable and also quite moving.

Brett McKay:

Speaking of that idea about how sibling dynamics can change over time, one of the recurring themes in your book is how no family is the same over time. So for example, the firstborn may experience an environment of very different parental resources. Maybe their parents are newlyweds and they’re still in college or just starting their careers, they don’t have a lot of money. And then the later sibling is born and the parents’ financial circumstances have changed because dad and mom have got great jobs. And so those two kids aren’t going to have the same experience. How much do changing family circumstances shape sibling outcomes?

Susan Dominus:

Yeah, this is the work of Dalton Conley who’s a sociologist who eventually became very much interested in the role of genetics and shaping personality, which is not the typical stance of a sociologist. That said, he has done really interesting work about how every sibling does kind of grow up in a different family depending on where the family’s finances are. So for example, he writes about families in which one sibling was able to go to private school and then the parents’ finances kind of fell apart and another sibling went to a not very good public school. And those kids might have very different outcomes. It’s especially true when that applies to a college education or even were the parents married or divorced? If you have one kid who’s 15 and the parents are married and then three years later that kid’s already left the house, but his younger sibling who’s now 15, the parents are fighting, they’re splitting up. That can set you on a really different path to, so every child grows up in a different home. That’s a statement that I think applies to my own family. And I think it’s not just that you are bringing your own perspective to how you interpret your family, but your family is changing over time. And that means that you at 12 are experiencing a different family than your older or younger sibling does at the same age.

Brett McKay:

And I imagine that can create guilt for some parents because they want to treat all their kids fairly and they feel like, well, I wasn’t able to give this one kid that opportunity that I was able to give this other kid. But I guess you can’t beat yourself up because there’s nothing you can do about that.

Susan Dominus:

Yeah, it’s interesting. I think in a way, I really hope that my book would be a relief to a lot of parents in that one of the main messages in the book is you have less control than you think over their fates because there is so much of an element of luck that comes into people’s lives, and that along with what kids are bringing to the table themselves, it’s true the decisions you make financially might have different effects on your kids. But as I said before, their environment is multifactorial and with the exception of whether you send your kid to college or not, I mean, we’re assuming all families here. We’re not talking about abusive families that can really do serious damage, but reasonably healthy loving homes. There’s a pretty wide range of behavior that really won’t affect the outcome. So for example, I think parents agonize over, should I co-sleep with my child or not?

Should I do gentle parenting or not? Am I attachment parenting or not? Should I punish my kids? How do I get them to be more disciplined in doing their homework? I think all this stuff has less of an effect than we think it does, at least on personality outcomes, how your child feels at any given moment. That’s important, but it’s also hard to predict how your child’s going to feel. So the example I always give in that regard is let’s say you have two kids who are very different, and both of them are naturally talented artists, and both of them have mothers who shower them with praise for their work and give them lots of art supplies and offer them art classes. One of those kids could grow up and say, I loved art. And then my mother smothered me and put so much pressure on me, and then I walked away altogether. And then the other one could at the Venice be an all give us toast that says, I just want to thank my mother who believed in me and showered me with classes and art supplies. So parenting is not one size fits all, which is why I always say that parenting advice should come with a caveat. Don’t try this at home. The best advice I give to parents is just know your child. You love the child you have, and go from there.

Brett McKay:

One dynamic with parenting that you did find that influenced children was these two types of parents. You often came across overcomer parents and thwarted parents. Tell us about that.

Susan Dominus:

Well, I think that this is something I saw in a lot of the parents that many of them were extraordinary themselves. So for example, just to return to the Bronte sisters, their father had grown up like dirt poor in Ireland child, I think of a tenant farmer was definitely a reach that he would ever end up at Cambridge, which is where he did end up getting his decree. So he had made tremendous leaps of class and education within one generation. We know they were very proud of their father, and they grew up reading the academic books that he won for prizes at Cambridge. But you see that a lot in a lot of the families I wrote about. But then on the other hand, you also have parents who are very talented but didn’t quite achieve what they wanted to. And I think they infused their children with it.

They sort of put that energy into their children. So Tony Kushner’s mother was a tremendous concert violinist, one of the youngest women ever to chair the violin in an orchestra and had to give up her career because she gave up her career for her children, basically, but really felt that she had been robbed of the potential for greatness. And Tony Kushner, the playwright, speaks a lot about how much she urged him on and how much her energy and talent kind of motivated him or Diane, this extraordinary director in New York and elsewhere, really one of kind generational talent. Her father had directed theater in Tokyo when he was in the military after the end of World War II, and loved, loved, loved it, but came back to New York, had kids, couldn’t quite figure it out, never really got there. But she says she remembers looking at a photo of him when he was in Tokyo right before play went on and having that same harried look that she has before a play, and realizing how much his dream was sort of completed by her.

Brett McKay:

And I think Joe Kennedy was another example. He was successful in business, and then he sort of took his ambition to the political realm. I think he wanted to be president, but that wasn’t the cards for him, probably because people didn’t like Catholics. And then he’s like, okay, if I can’t be president, then one of my kids is going to be president.

Susan Dominus:

If that’s true, that’s a great example. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

Brett McKay:

So something else you talk about, well, I was struck by this as I was reading the book, these high achieving families, these siblings that you highlight, the parents had really high expectations, but they were pretty hands-off. They weren’t helicopter parenting. Can you flesh out that dynamic because I thought it was really interesting is high expectations, but coupled with hands-off approach to parenting,

Susan Dominus:

I think that’s a great observation. The parents set this sort of ambient expectation that their children would work hard, would succeed, would throw themselves into whatever they did, and then they let them do it. There’s all this research that finds really good research that finds that when young kids are doing a puzzle, if their parent or even somebody on the research team intervenes and kind of solves the puzzle for the kid, the next time the kid sits down to do a puzzle, that kid is much less motivated. And I think that that probably applies not just to small children, but certainly to adolescents. And I think it’s very common for parents of my generation to feel this responsibility for their kids’ success and to really get in there with them and sit down and help them write their essays and knock it out with them and be hovering by their side. And I just think it makes it harder for the kid to do it on his own the next time, and they’re less motivated because they feel less ownership of it, and they’re not doing it for themselves. They’re doing it to please their parents, which is always going to be less motivating than doing something to please yourself.

Brett McKay:

So what do you hope people will take away after reading your book?

Susan Dominus:

One of the things we didn’t talk about is this idea of like, well, how do parents encourage their kids to dream big? And I think part of it is a little bit temperamental. I don’t know if you can become an optimist if you’re not naturally one, but the parents and the families I wrote about really were true optimists. And they said things to their kids like, with God’s help, all things are possible, or just all things possible, or The sun shines on all of us, meaning there’s opportunity for everyone. And I think those kinds of inspiring messages, as hokey as they are, I think kids need to hear it. And at the same time, I feel that it’s my hope that parents would tell their kids, look, if you want to reach for the moon, you want to shoot for the moon? I am right there with you and go for it. I’ll support you and you should. That said, if you don’t want to shoot for the moon, that’s okay too. You know what I mean? In other words, life is not all about achievement, and I love you for who you are. It’s just to meet. It’s about creating a sense of possibility should that kid want to aim really high.

Brett McKay:

Yeah. Well, Susan, it’s been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Susan Dominus:

Well, I frequently write, I’m a staff writer at the New York Times Magazine, so obviously nytimes.com. I’m on Instagram almost never anymore @suedominus. And my book, The Family Dynamic can be found obviously on Amazon, but also at independent bookstores everywhere.

Brett McKay:

Fantastic. Well, Susan Dominus, thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure,

Susan Dominus:

Brett. Thank you so much for having me on. I really loved talking to you,

Brett McKay:

My guest was Susan Dominus. She’s the author of the book, The Family Dynamic. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Check out our show notes at a aom.is/familydynamic where you can find links to resources so you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition to the AoM podcast. Make sure to check out our website at artofmanliness.com where you’ll find our podcast archives.

Make sure to also check out our new newsletter. It’s called Dying Breed. You can sign up at dyingbreed.net. It’s a great way to support the show directly.

As always, thank you for the continued support. This is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only listen to the podcast, but put what you’ve heard into action.